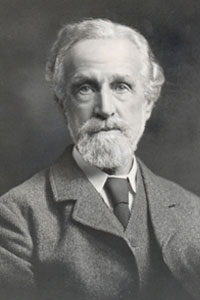

Sir Thomas Smith: Great Ormond Street's Famous Victorian Surgeon

“Sir Thomas Smith is dead, and in him we have lost not only a great surgeon, but a king among men”

This judgement – by one of Thomas Smith’s old pupils – says a great deal about Great Ormond Street’s first consulting surgeon. Tom Smith was born in Blackheath in Kent in 1833, the sixth son of a goldsmith. When his father went bankrupt in 1850, he went to work for family friend, James Paget (later to become surgeon-extraordinary to Queen Victoria) at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, thus becoming one of the last of the hospital apprentices. He did not over-exert himself in studying, preferring hands-on experience and observation to reading surgical textbooks. In fact, he claimed that he never opened a book on surgery until after he had passed his Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1854. He was immediately offered the post of house surgeon at the two-year-old Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street, but knee trouble forced him to resign after a few months. He worked privately for Paget thereafter, and took groups of medical students to Paris each Easter to teach them operative surgery. In 1859 he published a little book, A Manual of Operative Surgery on the Dead Body.

Having made a name for himself as an excellent dissector and a swift operator, Great Ormond Street lured him back in 1861, and he remained as assistant surgeon until 1868, becoming surgeon, and consulting surgeon thereafter. While there, he wrote a paper on using horsehair instead of wire in suturing wounds. One of the dogs on whom he had experimented using horsehair was thought to have died under chloroform, and the body thrown out. Next morning the animal was on his doorstep, waiting to be let in. He was brought indoors, and lived very happily as a family pet until his death (from natural causes) some years later. Tom Smith developed an interest in operating on hare lip cases and he was such a fast worker that people used to attend his operations with a stop watch in their hands. His record for removing a kidney stone was thirteen seconds from the first cut to the sound of the stone plopping on the dish. At Great Ormond Street, he invented a gag which enabled chloroform to be administered while the operation for cleft palate was being performed, thus enabling him to treat children at a younger age; before this, surgeons were compelled to restrict this operation to children old enough to co-operate. The patients at the hospital regarded him as a sort of perpetual Father Christmas, especially when he made his entrance to the ward deliberately sliding along the sister’s highly-polished floor.

In spite of publishing at the age of 26, he never had much time for surgical publications, claiming it was the men who never got the cases who wrote the books. He liked to see things for himself rather than read about them in books, so he spent part of his summer holiday in 1875 in Edinburgh, studying Lister’s practice. When he came back to London, he was the first surgeon at the Hospital to try antiseptic surgery, although he was not such a devotee that he stopped licking the end of the horsehair before threading the suture needle.

Smith married and he and his wife had nine children (one of whom married a Great Ormond Street man – Archibald Garrod) before her premature death at the age of just thirty six. He declined the Presidency of the Royal College of Surgeons on the grounds that he was bringing a large family up on his own, and set up the Samaritan Maternity Fund at Bart’s in memory of his wife. When he retired in 1898, he took up golf, fishing and other country pursuits. He was appointed surgeon-extraordinary to Queen Victoria in 1895 (following in the footsteps of his old teacher), and assisted Sir Frederick Treves in operating on King Edward VII’s abscessed appendix in 1902. Already a baronet, he was made a Knight of the Victorian Order in 1901 for his work with officers wounded in the Boer War.

Tom Smith was a surgeon of occasional genius and a colourful character. However, he was also a compassionate man who took time and trouble to get to know those who came under his knife. The last word we shall give to his old pupil, “Of all that one remembers of him, nothing is more vivid than his passionate desire to do the right thing for his patient.”