Cromwell House – a haven for the patients

Cromwell House – a haven for the patients

By 1868, the governors of the Hospital for Sick Children had long realized that some patients were being re-admitted to the wards soon after discharge, because their home circumstances mitigated against continued recovery. Since it opened in 1852, the hospital had sent children to convalescent homes, generally at the expense of hospital supporters. Children were regularly transported to Mitcham, and to the seaside at Margate, Brighton, Torquay and Eastbourne, in the hope that rest and country or sea air would help them regain health and strength.

The Hospital had always stated quite categorically that it was not an institution for ‘sickly’ children, but the fact was that many patients were admitted to the hospital suffering from chronic ailments, such as tuberculosis in its various forms. After a few weeks’ treatment, these children were not ready to go back to their overcrowded homes, but they were taking up precious bed space. The answer was to open the Hospital’s own convalescent home, near enough to make visiting and transporting the children feasible, but away from the foul coal-filled air of central London.

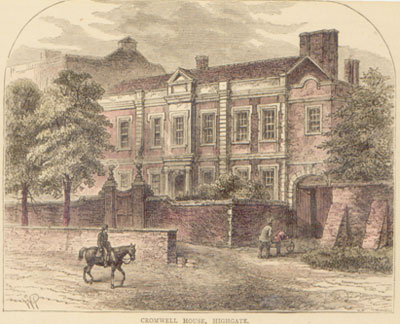

After months of searching, the governors settled on Cromwell House, an early 17th century mansion in Highgate Village. It had space for 20 beds for convalescents, and 32 for chronic cases (12 medical and 20 surgical). The Hospital for Sick Children’s publicity machine ensured that articles on the new facility appeared in The Illustrated London News, The London Mirror and other journals. Five open days were held before the official opening of the facility in June 1869, and hundreds of supporters had the opportunity to inspect the venture, and to dig deep into their pockets for it.

After months of searching, the governors settled on Cromwell House, an early 17th century mansion in Highgate Village. It had space for 20 beds for convalescents, and 32 for chronic cases (12 medical and 20 surgical). The Hospital for Sick Children’s publicity machine ensured that articles on the new facility appeared in The Illustrated London News, The London Mirror and other journals. Five open days were held before the official opening of the facility in June 1869, and hundreds of supporters had the opportunity to inspect the venture, and to dig deep into their pockets for it.

The numbers treated crept up, and by 1885, Cromwell House provided care for 98 convalescent and 152 chronic patients at any one time. Convalescent patients were generally those who had undergone treatment at the main hospital, and needed to rebuild their health and strength before returning home. These children could be (and until the First World War, frequently were) sent to private establishments. However, such places did not usually admit patients under the age of four, or those who required

ongoing medical attention for a chronic complaint. Thus Cromwell House was used for the youngest convalescing patients, and those recovering from surgery or suffering from long-term illnesses.

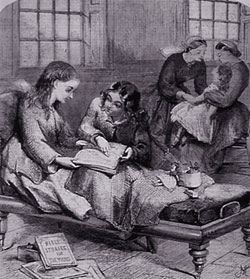

From 1870, parents were allowed to visit their children at Cromwell House on Sunday afternoons. The children could enjoy the house and its gardens, as if it was a large residential nursery school. They spent as much time out of doors as possible, and the grounds not only had vast lawns to act as a playground, but swings and chutes. Local visitors brought flowers and fruit from their gardens, and a barrel organ (complete with dancing monkey) played outside the house in the summer months. The lady supporters of Highgate came to visit regularly, and taught the patients how to read and write, and kept the fractious ones amused while the nurses got on with the hard labour of the house.

From 1870, parents were allowed to visit their children at Cromwell House on Sunday afternoons. The children could enjoy the house and its gardens, as if it was a large residential nursery school. They spent as much time out of doors as possible, and the grounds not only had vast lawns to act as a playground, but swings and chutes. Local visitors brought flowers and fruit from their gardens, and a barrel organ (complete with dancing monkey) played outside the house in the summer months. The lady supporters of Highgate came to visit regularly, and taught the patients how to read and write, and kept the fractious ones amused while the nurses got on with the hard labour of the house.

The staff at Cromwell House enjoyed more freedom, but also more individual responsibility, than their Great Ormond Street counterparts. Each nurse on duty during the day had to look after between nine and twelve children. They started work at 7.30 am, and did not finish until 6 or 7 in the evening. They had to wash and dress their children, dress the wounds, take temperatures, administer medicines, make the beds,

The staff at Cromwell House enjoyed more freedom, but also more individual responsibility, than their Great Ormond Street counterparts. Each nurse on duty during the day had to look after between nine and twelve children. They started work at 7.30 am, and did not finish until 6 or 7 in the evening. They had to wash and dress their children, dress the wounds, take temperatures, administer medicines, make the beds,

serve the meals, and in every way attend to their patients’ comfort. They also had to sweep and dust the ward, scrub tables and lockers, wash bandages, rinse soiled linen, and once every three weeks do the crockery washing-up after meals (except breakfast) for a week. In summer they had to carry the children to the garden and bring them in again.

Sometimes as many as 18 children had to be woman-handled out of doors, as the Medical Officers attending Cromwell House insisted on the children being in the open air as much as possible. The nurses had a magnificent ten minutes for lunch, and twenty minutes for their dinner. At four each afternoon they gave the children their tea, after which they put them to bed, which was a process that could easily take two or three hours. A surgeon and a physician visited twice a week, on which days the nurses did not finish until 7.30 in the evening. Every Thursday one nurse was delegated to take and bring back children to the main hospital at Great Ormond Street.

The hospital tried to make life easier for the nurses by restricting the sort of ailments that would be deemed suitable for Cromwell House. All children admitted had to be able to walk, and to partly feed and dress themselves. While these regulations certainly restricted the numbers of children admitted, the biggest filter was the fact that parents were expected to pay two and sixpence in transport costs to get their child to and from Highgate, and sixpence a week for washing. Three shillings (15 pence in today’s currency) was a lot of money at a time when the average London labourer earned just twenty shillings (one pound) a week, and it is not unreasonable to assume that the cost of Cromwell House denied many children access to its benefits.

The hospital tried to make life easier for the nurses by restricting the sort of ailments that would be deemed suitable for Cromwell House. All children admitted had to be able to walk, and to partly feed and dress themselves. While these regulations certainly restricted the numbers of children admitted, the biggest filter was the fact that parents were expected to pay two and sixpence in transport costs to get their child to and from Highgate, and sixpence a week for washing. Three shillings (15 pence in today’s currency) was a lot of money at a time when the average London labourer earned just twenty shillings (one pound) a week, and it is not unreasonable to assume that the cost of Cromwell House denied many children access to its benefits.

Cromwell House continued to operate until the early 1920s, when it became clear that the old mansion was no longer suitable for long-term convalescent care, and that metropolitan London had crept up Highgate Hill, enveloping the house and garden in pollution and traffic noise. A new mansion (complete with extensive parkland) was found near Epsom in Surrey, and Tadworth Court became the new convalescent branch of The Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street. The main house was partly given over to wards, but mostly for offices, and single-storey pavilions were built in the grounds to house non-ambulant patients more easily.